Lydia was larger than life.

Her paintings, installations, lectures and scholarship were all intertwined, embodying her probing and profound intellect and her far ranging quest to decipher modern culture through the art of Pablo Picasso and other artists.

Born into a Jewish family in Focsani, Romaniain 1926, Lydia Csato survived the German occupation of her country during World War II and went on to study art and the law at the University of Bucharest. By the 1950s, she was one of the most successful painters working in the Social Realist style mandated by Romania’s Communist government. Many of her works were purchased by the government and exhibited at the national museum in Bucharest. Despite her renown, Lydia was opposed to the tyranny of the Romanian government, and in 1960, she fled the country in the middle of the night.

Born into a Jewish family in Focsani, Romaniain 1926, Lydia Csato survived the German occupation of her country during World War II and went on to study art and the law at the University of Bucharest. By the 1950s, she was one of the most successful painters working in the Social Realist style mandated by Romania’s Communist government. Many of her works were purchased by the government and exhibited at the national museum in Bucharest. Despite her renown, Lydia was opposed to the tyranny of the Romanian government, and in 1960, she fled the country in the middle of the night.

Lydia went to Paris where her discovery of Picasso’s art seemed an epiphany. The radically innovative ways in which Picasso depicted reality, seen and unseen, opened up vistas that Lydia was seeking and would continue to explore for the rest of her life. While climbing the Acropolis in Athens, Lydia met her future husband, American historian of Science Daniel Gasman. The couple moved to New York in 1963. Here, Lydia enrolled in the art history graduate program at Columbia University. She wrote a ground-breaking dissertation, Mystery, Magic and Love in Picasso, 1925 – 1938: Picasso and the Surrealist Poets which would transform the field of Picasso scholarship.

Although her dissertation became famous in scholarly circles and continues to be mined as a resource, Lydia never published it as a book. She allowed a contract with Yale University Press to expire as she pushed beyond the boundaries of her original thesis to explore the entirety of Picasso’s career and larger history. Lydia was haunted by the timeless questions of good and evil, and how the twentieth century, with all of its technological “advancements,” could be so fraught by war and terror. As she deciphered Picasso’s writings and drawings, Lydia found that he wrestled with the same ideas. For example, she understood the central dilemma of Picasso’s Guernica as how does the sky — the traditional seat of the sacred — become the source of death raining down bombs from above.

Lydia continued to explore such themes in 1981 when she joined the art history department at the University of Virginia. It was there in 1984, that I and Victoria Beck Newman, co-director of the LCGA, met Gasman as graduate students. Charismatic and beautiful in both intellect and personality, Lydia became our mentor. We had the fortunate and unforgettable experience of working with her on our doctoral dissertations and as teaching assistants for many years. In her legendary classes, Lydia continued to explore the role and meaning of angels and airplanes in modern art from Picasso to the contemporary artist Anselm Kiefer. One semester she explored “Angels and Airplanes,” following the angel in art and religion and popular culture from antiquity to Anselm Kiefer’s use of wings and airplanes.

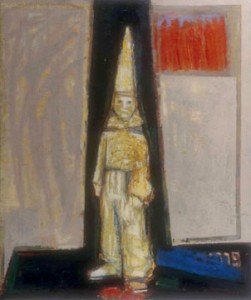

She also focused on these questions in her painting, The Angel of History, (referencing works by Paul Klee and Walter Benjamin) with an aluminum wing, an antithetical blue wing, ominous black masses and an angel identified as her beloved nephew who died on an air force mission when his parachute failed to open. Working on macrocosmic and microcosmic planes at once, Lydia’s work was personal and universal. It was uncanny the way she seemed to time travel in her portraits, painting people as they would look later in their life or even as they looked in the past. She painted and assembled a magnificent mural on her apartment wall of her mother, Sara, as a young woman.

In Anthropomorphic Brushstrokes, Lydia’s brushwork took on the forms of birds and fish floating without gravity through space, or a motherly form encircling a glowing yellow child, all about union and perhaps reunion.

Lydia’s last painting, Landscape as Home, similarly portrays an Edenic garden space with pulsing blobs of bright green trees sprouting from incandescent whites, glowing yellows. She incorporates a cut out figure with eyes closed from an Odilon Redon painting in its midst. The image is idyllic, hopeful yet quiet and full of mystery. In spite of living through the Holocaust and witnessing the extremes of evil and suffering in our century, Lydia’s life, art and writings embodied hope and love and joy. Her paintings, in this sense, were Matissian gifts and wagers on life instead of death.

Lydia Gasman retired in 2001 and died in 2010 at the age of 84. Her paintings are now featured in Picasso, Lydia and Friends, 2014 at Les Yeux du Monde Gallery, 841 Wolf Trap Road, Charlottesville. The show, running to October 5, is held in association with the Lydia Csato Gasman Archives for Picasso and Modern Studies.

Gasman’s work is exhibited alongside etchings and lithographs by Picasso, and works in all media by “Friends” William Bennet, Anne Chesnut, Dean Dass, Sanda IIiescu, David Summers and Russ Warren.

–Lyn Bolen Warren, Founder and Director, Les Yeux du Monde Gallery, and co-director with Victoria Beck Newman, Lydia Csato Gasman Archives (LCGA).

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.