Rick Weaver seems an artist equally interested in what can and cannot be seen. Whether working with paint brushes, carving tools or modeling clay, his creations blend the subject at hand with what he imagines is missing.

Initially trained in classical drawing and painting, Weaver now concentrates on sculptures, life size as well as those larger and smaller. He’s currently completing a commission of a Native American boy for an art association in St. Augustine, Florida. He’s shaping the 54″ statue in wax eventually to be cast in bronze.

The young Native American holds a palm frond, his expression hopeful and hesitant. Weaver recruited his two young nephews to pose briefly but otherwise draws on his personal perceptions. “The Association wants a piece to reflect St. Augustine’s past,” he says. “This is my imaginary thinking of a native child welcoming whoever’s coming on shore, and all the positive and negative things that will come along with that.”

In 2013, Weaver won the commission for a life size portrait of Federal Judge J. Waites Waring of South Carolina, a civil rights activist who in 1951 dissented against segregation, a decision leading to the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education ruling three years later. Judge Waring died in 1968. The competition for his statue called for sketches of the Justice to be seated. Weaver submitted sketches of Waring both seated and standing, feeling that having the activist stride forward showed him to better advantage. The judges ultimately agreed.

Although photographs of the Justice were available, Weaver used them only sparingly. “I looked at them and tried to form my idea of what was most distinctive about him visually, the shape of his head, the cast of his eyes. Was he heavy lidded? How did he hold his mouth? I tried to identify with him as a person, the things he went through, things that meant something to him. It was a combination of putting his characteristics together with what I felt was most emotionally and psychologically distinctive about him.” Waring’s 6’ 3” statue now stands in the garden of the Federal Courthouse in downtown Charleston.

Weaver put his imagination into even fuller play when making a portrait of African American John Chavis. “There were no authoritative photographs of him. So (the imagery) came more from me. I actually found a guy on the downtown mall who sort of fit my idea of what I thought Chavis would look like. I followed him around the CVS and eventually asked him if he’d pose. He was intrigued and agreed to do it.” Again, Weaver read up on his subject and let his creativity fill in the gaps.

“Since there’s no known image of Chavis, I wanted something that felt like my idea of the kind of person he was. I think he was incredibly determined and resilient. He had to walk between two worlds – a white world and black world. For his time, he did an incredible thing as an African American.

“From what I’ve read, he was confident of his own abilities and his intelligence. I was looking for something that was introspective more than anything else.”

Weaver’s thoughtful likeness of John Chavis was commissioned by Washington and Lee University in 2005 and is exhibited in their John W. Elrod Commons.

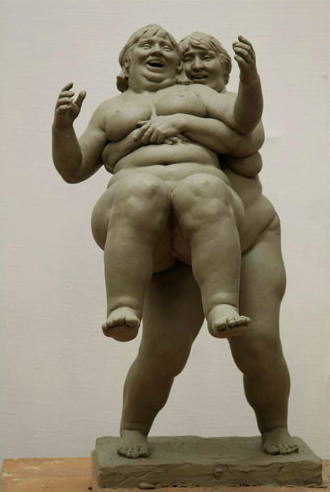

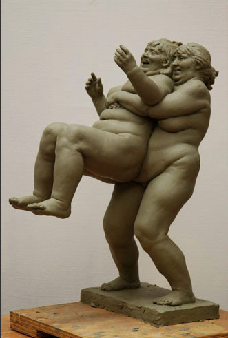

While Waring and Chavis are imagined as serious and meditative works, Weaver also produced an earlier series of smaller clay statues depicting oversized, nude men and women cheerful, if not gleeful, in their pursuits.

Weaver, a long, lean and reticent man, says he did not intend his figures to comment on weight itself but their shapes instead. “Dealing with really full forms seemed much more interesting to me than dealing with thin, skinny forms. The idea that these figures bore burdens or weight, I think that’s something we can all identify with; it may not be physical weight but we’re all bearing some sort of burden. So they became really self-referential, as I guess all my work does become.”

If weighted with burdens, Weaver’s figures do so with humor and a spirit of play. “I didn’t want the weight to do anything negative per se,” he says. “It’s something that creates a challenge that you have to bear and deal with and persevere through. I saw it as something, in the last analysis, as very positive.”

Some nudes heft up others. “The visual idea of a heavy figure lifting another heavy figure seems potent in some way. I start and think about the possibilities as I work on it. Usually the image comes first and then the narrative develops.”

“I feel there’s something ultimately affirming about life and what I do is affirming and about persevering, the good with the bad and hopefully is ultimately beautiful and positive.”

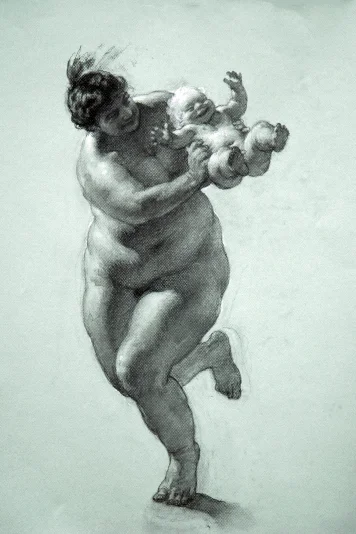

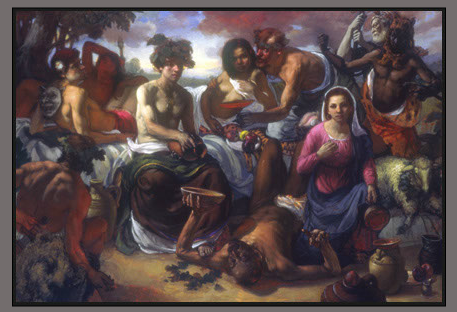

Weaver’s drawings and paintings show equal exuberance for the full figure, perhaps inspired by his Baroque favorites when he studied at the National Academy of Design and the Arts Students League.

“When I went to New York, I wanted to learn how to draw and paint naturalistically. Back in the early 80s, we were woefully out of fashion but there was a core of us who were pretty dedicated to trying to learn traditional precepts for painting and drawing from life so those were the people I studied with,” says Weaver.

Among his influential instructors were Robert Beverly Hale for anatomy, and Ted Seth Jacobs, Ron Sherr and Harvey Dinnerstein for painting. He later earned a Master of Fine Arts from the University of North Carolina-Greensboro under the tutelage of sculptor Billy Lee. He also praises contemporary realist Antonio Lopez Garcia.

Weaver admits that his first tries at figure drawing were copying Marvel Comics super heroes and the fantasy figures of science fiction illustrator Frank Frazetta.

“I started drawing and painting because one of my primary interests was in the figure, looking at Baroque painters like Rembrandt, Caravaggio, Velazquez, and Vermeer, artists who were interested in a more naturalistic light and how that fell on the figure. I’ve done landscapes and cityscapes, still lifes, and watercolor sketches when traveling, but my passion has always been the figure.”

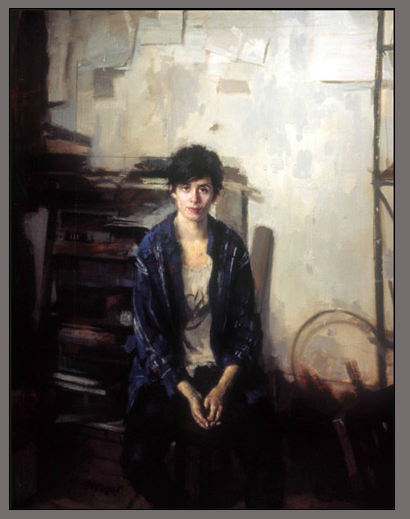

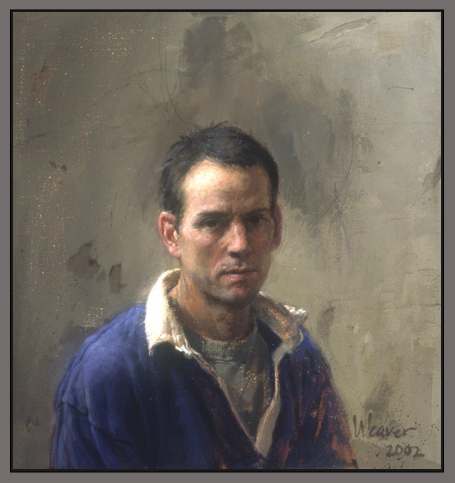

Weaver’s portraits show his continuing devotion to the figure, particularly the human head. In 2006 his portrait, Maggie Sullivan, was chosen as an Outwin Boochever Portrait Finalist to be shown at The National Portrait Gallery. His work has been exhibited nationally in galleries from Chicago to New York.

The portrait’s model was a UVA student who posed periodically at the McGuffey Art Center in Charlottesville. “She had an interesting psychological atmosphere around her. She was quiet and there was something potent about her that was interesting to me,” Weaver says.

“I don’t think it’s possible to capture the essence of someone. I try to look for something distinctive, some emotional quality I can recognize in myself as a kind of ‘swing thought’ to keep me focused as I worked through a painting.”

Weaver also found inspiration in the Biblical themes of his Baroque painters. “I’m not traditionally religious person but I’ve looked at a lot of religious art, and Bible stories interest me because of their commentary on humans and human morality; some are very compelling. You see this in Caravaggio and Rembrandt. Vermeer’s work doesn’t tell necessarily overt Christian narratives, but there’s a very devout feel to his work, the way he treats light and space. There’s something sacred about his work, a stillness, a meditative feeling.

In Mary on Naxos, Weaver combines both religious and mythological subjects — the myth of Ariadne and Christian iconography. “Putting the two together,” he says, “created some questions that seemed interesting to me to think about.”

More questions arose in Falling Figures, a particularly intriguing painting from a series picturing men, women and children a jumble in space. “It’s completely from imagination. I’m not sure where it came from,” says Weaver. “Like most ideas that I find interesting in painting or sculpture, there are two possibilities that are kind of opposing one another. Here, I’m trying to organize these figures that are essentially in a state of chaos. The figures are seen as falling or coming up…a feeling of control or loss of control. I’m not exactly sure what these oppositions mean but it’s a beginning place that I can work with as I paint the picture. I’m not sure what kind of resolution there is….”

As he considers, Mozart plays in the background. Rain taps on the tin roof.

With more questions to come, Weaver offers parting thoughts: “A friend said, ‘the artist’s job is not to answer questions but pose a really compelling question.’ Ultimately what I’m doing is posing a question for myself, and in the act of painting (or sculpture), I try to deal with the question on some level. I’m not sure if I ever answer it completely..I don’t know if I want to..”

Rick Weaver, the son of an Army officer who liked to draw and paint, has lived in Thailand, Italy, Germany as well as on many bases in the U.S. For the past 13 years, he has lived in Charlottesville with his wife, Tracy, and their son, Max. An adjunct associate professor at Piedmont Virginia Community College, he also teaches privately and conducts workshops at The Art League in Alexandria, VA. Visit richardweaver.net to see more of Weaver’s work.

— Elizabeth Meade Howard, Art Editor

Follow us!

Share this post with your friends.