Growing up on a dairy farm in Northern New York, in Southern Jefferson County during the 1960’s meant, for my family, doing most of the work with our physical bodies. With a maximum of 25 dairy cows, one tractor, a pick-up truck and a few older pieces of machinery that came with the farm when we purchased it, my parents and we older children eked out a living. Our cows were rotated from field to field during warmer months after the hay had been harvested, and during the winter they were kept in the barn, and fed the hay and some grain to keep them well-nourished and producing milk. Many of the cows which were pregnant and produced Spring calves, were dry of milk during the long winter.

Growing up on a dairy farm in Northern New York, in Southern Jefferson County during the 1960’s meant, for my family, doing most of the work with our physical bodies. With a maximum of 25 dairy cows, one tractor, a pick-up truck and a few older pieces of machinery that came with the farm when we purchased it, my parents and we older children eked out a living. Our cows were rotated from field to field during warmer months after the hay had been harvested, and during the winter they were kept in the barn, and fed the hay and some grain to keep them well-nourished and producing milk. Many of the cows which were pregnant and produced Spring calves, were dry of milk during the long winter.

Like members of cattle cultures the world over, our relationship with the cows went deep, was time tested. We cared for them; they gave us a living. We intertwined our roots with the animals in a complex system which gave our lives structure and purpose. We could not easily untie this knot of life which the farm fostered. And though we didn’t analyze it; the tie was something we felt and responded to every day.

For the animals and the land to nurture us necessitated long range planning. The rains and heavy snowfalls accumulating in clouds over the Great Lakes to the west of us determined our work from day to day. If the weather could be anticipated, we could do better farming, but the dynamic patterns blowing down out of Canada altered air temperatures hourly. We adapted, added or shed clothing, changed our schedules. We felt the exhilaration of change rising over the curve of our horizon, but we had to survive by the only way of life we knew. We bent to the whim of the elements as a part of life larger than ourselves.

***

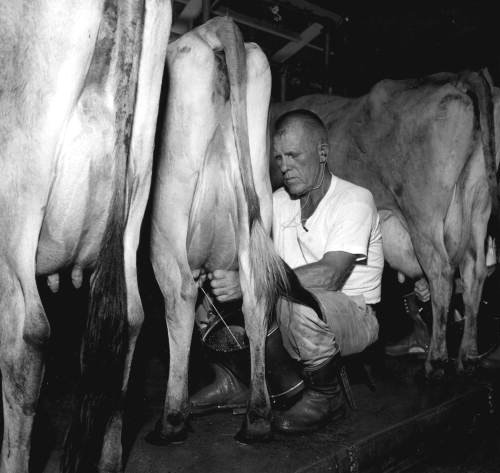

A toddler, I stand behind the cows and watch our mother wash their bags. When she squeezes the milk from the cow’s udders, a straight white line shoots from the nipple to the bottom of the pail. I like the hard sound it makes when it hits the pail. Then I walk down the row to see Dad. My father milks very fast. The sound grows muffled and foam rises like a white pillow to the top of the pail.

A toddler, I stand behind the cows and watch our mother wash their bags. When she squeezes the milk from the cow’s udders, a straight white line shoots from the nipple to the bottom of the pail. I like the hard sound it makes when it hits the pail. Then I walk down the row to see Dad. My father milks very fast. The sound grows muffled and foam rises like a white pillow to the top of the pail.

Ages three and four, in our cotton shorts and blouses, Gloria and I run behind the cows, laughing when their pee pours out of them high above us. A tail begins to rise, and we squeal and dart away as the yellow waterfall splashes into the gutter and onto the cement floor. Giggling, we dodge to one side just before the drops catch us. The cows peer sideways at us with their big eyes. Our mother gets up from her stool and dumps the milk from her pail into a steel strainer over the milk can in the center of the floor.

One evening while they are milking, we go over to the hay loft and I climb the ladder. The loft is empty and the ladder stops at a beam about nine feet up. I stand on the beam and look down on my sister.

“You can’t do this,” I brag. “Don’t even try.” The part in her hair is visible from up here. She looks smaller than ever and cries out,

“Come down! Come down or I’ll cry.”

I try to step back onto the ladder and fall to the wooden floor in front of my sister. We’re both screaming. My bottom teeth have cut through my lip; my mouth is bloody; my knee is bleeding. My body hurts, but I know it will hold together. Both my parents appear and pick me up, turn me over. No bones broken, they say. I don’t know what bones are.

When I’m eight, Dad is pleased I want to learn to milk. I sit on the stool beside the cow and try to hold the smallest pail between my knees. It jumps out and rattles under the cow. She steps sideways. I freeze to the milk stool. Dad grabs the pail and tells me to get a good grip on it with my knees…Now curl your fingers, squeeze. Squeeze and pull. First one hand then the other. Front quarters first. My hand on the udder, below the soft, full bag. I begin, and tiny streams squirt into the pail out of the body of this long-legged young Guernsey. She likes to be milked. She never kicks, and turns her head in the stanchion to see who I am and what I am doing to her back there. I ask her to be patient. I tell her she is a good cow, a good girl, like me. After half an hour, a quart of milk is in my pail. I am exhausted. Dad comes back to finish the job. Every evening now we do this. I love this cow.

A year goes by and I’m allowed to bring the cows in for milking. They rush into the barn driven by adults. I am supposed to direct them to the right stanchion, turn them, but they don’t listen to me or see my arms waving. They don’t turn, go where they please. I am trapped between two of them, their backs taller than my head. Their sides squeeze the breath out of me, and if I push against them nothing happens. When one moves I duck between the stanchions into the feeding space in front of them. I’m sweating all over. My body is tense in my overalls and red shirt. When I look around all the cows are suddenly in stanchions, heads down, eating their sweet grain. My father is closing each gate shut around their necks. He spots me where I’m waiting.

“There you are,” he says.

***

Five years later, our twenty-five Holstein and Guernsey cows gave us six cans at each milking in their good season. The milk-man, a neighbor, loaded our cans onto his truck each morning, and if my parents were running late when he arrived, he waited for them to finish and talked with my father while they watched the last drops run through the strainer.

The still-warm morning milk went onto the truck along with the cans extracted the evening before and cooled overnight in a vat of cold water. Each evening, our father hoisted the full cans into the cooler, the rope-like muscles in his tanned arms bulging, as he swung the cans over the lip of the cement vat and let them slip into the cold water. When he was busy, I, or my sisters, helped Mom wrestle the hundred and forty-pound cans one by one over the edge of the cooler and into the water. Cold water splashed into our faces and onto our clothes. We didn’t mind; we had created a ritual over the moment. Our parents’ worry about selling enough milk to support us strengthened our satisfaction in helping put the milk to cool.

In this northern climate, the cows stayed in their pastures at night during spring and summer and into early autumn. At five o’clock in the morning Dad rose and dressed in his overalls and work shirt, grabbed a quick cup of coffee Mom had made, and walked to gather the cows. He called them along the way and except for a straggler, or a cow about to give birth, they came to meet him, anxious for their grain and to be relieved of their milk. They knew their job and what their reward would be.

In this northern climate, the cows stayed in their pastures at night during spring and summer and into early autumn. At five o’clock in the morning Dad rose and dressed in his overalls and work shirt, grabbed a quick cup of coffee Mom had made, and walked to gather the cows. He called them along the way and except for a straggler, or a cow about to give birth, they came to meet him, anxious for their grain and to be relieved of their milk. They knew their job and what their reward would be.

When I turned thirteen, the job of getting the cows into the barn each morning became my responsibility. Across the dew-wet fields, I walked to rouse the herd. Moving out into night-cooled air, my legs tingling, eyes adjusting to shadows and changing streaks of light, I searched for the huddle of cows. Some were already on the way to the barn when I passed them, and I murmured a praise for their help. If a cow was about to freshen and was not with the herd, if she had dropped the calf behind a bush and was guarding it, I did not approach her. Dad would go out later, with one of us to help him, and drive the reluctant mother, murmuring and bellowing to her offspring, back to the barn.

Each cow had a distinct personality. Jubliee held up her milk unless she had a dish of grain to eat while we milked her. Nellie spent a winter in a stanchion with a faulty watering cup which filled only when its lever was jiggled or pushed a certain way. She learned to press her horn expertly on the lever, fill her cup, drink it, and refill the cup again and again until she was satisfied. When Blossom became ill, the Vet prescribed a can of tonic with a long spout. She soon learned to recognize the can, and would curl her upper lip each time they approached her with the medicine. Lop Horn acquired her name because one of her horns was growing downward, dangerously close to her eye. She was ostracized by the herd, bunted and driven off whenever she approached the other cows. After she was de-horned, the other cows relented and allowed her to eat beside them.

Cows are hay burners. They eat constantly, consuming alfalfa or whatever tasty, mineral- filled grass their long muscular tongues can grab in the meadow. However much hay we put into the barn, they ate all of it and then some. What goes in one end of a cow comes out the other. Soft, swishy manure. Stinking, splattering, green-brown manure from spring meadows. Soupy manure pies with drying crusty tops hidden in grass to be stepped in. Their bowels emptying while they walked, liquid manure splashed onto our legs as we drove the herd across the field or up the lane to the barnyard. Manure filled the gutter behind the cows in the stable, and had to be shoveled and cleaned away twice a day. One way or another, their dung ended up on the land. The tons they left in the barn during milking time, (or during the winters when they lived in the barn for months), we scooped away and shoveled into a wheelbarrow, and wheeled it along narrow planks of wood onto the manure pile behind the barn, and dumped it. Fresh cow manure is wet and very heavy, and as a teenager, a shovel-full could bend me double if I hadn’t calculated carefully how much I could lift.

One of our neighbors had technology in the form of an electric track in the bottom of the gutter which moved the manure out a chute at the end of the barn, where it plopped into the manure spreader or “honey wagon.” When the spreader was full, he hooked his John Deere tractor to it and took the poop for a spin through the field, the efficient “beater blades” at the back spewing it out across the land. In a matter of minutes, what came from the earth went back onto it, and that phase of the work was finished. The nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium in the manure ensured a good crop of new hay next season. The soil’s structure would build up with every spreading.

But at that time, my parents couldn’t afford a manure spreader. For a while we had one which could be fixed and made to work for a week or so before going to pieces again. Sometimes we borrowed one.

The manure pile beside our barn was already half the size of the house when we moved to this farm, in the township of Lorraine, when I was thirteen. Despite my father’s efforts to spread some of it, after two years, the pile had grown until the narrow planks leading to it from the barn sloped up-hill. We looked down thirty feet to the ground. Each year the inspector from the milk plant told my father the pile would have to disappear if he wanted to continue selling milk to the company. Each year my father fussed and fumed over the job, and did as much as he could by himself to spread it on the land. Finally, after two years, a final warning came from the milk plant. The rules could not be bent any more. The manure pile was too big and too close to the barn. We had two weeks to remove the whole manure pile, or we would be “put out of the plant,” and unable to sell milk.

The manure pile beside our barn was already half the size of the house when we moved to this farm, in the township of Lorraine, when I was thirteen. Despite my father’s efforts to spread some of it, after two years, the pile had grown until the narrow planks leading to it from the barn sloped up-hill. We looked down thirty feet to the ground. Each year the inspector from the milk plant told my father the pile would have to disappear if he wanted to continue selling milk to the company. Each year my father fussed and fumed over the job, and did as much as he could by himself to spread it on the land. Finally, after two years, a final warning came from the milk plant. The rules could not be bent any more. The manure pile was too big and too close to the barn. We had two weeks to remove the whole manure pile, or we would be “put out of the plant,” and unable to sell milk.

This warning came during the summer, thankfully. My father asked our neighbor for the use of his spreader, but it was broken and wouldn’t be repaired in time to meet our deadline. The only alternative, Dad told me, was to move it by hand using a manure fork. He went to the farm supply store and bought a second one. Eight hours a day for the next fourteen days, the two of us shoveled cow manure onto a wooden wagon hitched to an old orange Allis Chalmers tractor. Dad drove the tractor and wagon into the fields and together we shoveled the manure onto the land. By the end of the first day, my arms ached and I took aspirin for relief that night. By the second and third days, I had sharp pains in the muscles and ligaments of my forearms, and blisters forming on my hands. At night my mother helped me wrap hot towels around both arms which relieved the pain enough so I could sleep. Dad was having a more systemic reaction to the methane and nitrogen gases rising out of the pile. During the evenings he vomited and complained of severe headaches, but went back, cursing, to the formidable task each morning. From time to time, my mother and my sisters left their own chores and came out to help and I rejoiced in the relief and ran into the house and escaped into TV for an hour or two. But, inevitably, I returned to the manure and rode on a blue tarp covering the full wagon of shit back to the field and tossed it onto the ever-greening meadow.

Even though I wore gloves, the blisters on the palms of my hands grew and wept. Twice a day I dressed them with an ointment and gauze, put my gloves back on and went back to work. Large scabs formed over the blisters, and each morning and evening when I milked the cows, the scabs cracked and bled. My usual meditative hours with the cows became excruciating, but somehow, perhaps by leaving my hands uncovered overnight, I managed to prevent any infections from taking over, and each morning, my father and I took our places on the slowly dwindling pile until there was none of it left. We had covered several large meadows with the life-sustaining gift. The manure had lain in the ever-growing pile for years. Below the top two feet, it had composted itself and the organic matter housed many species of bugs, worms and microorganisms that would work their way down into the soil of the meadows. When Spring came, a thick green carpet of grasses would be pushing through last year’s leftover stalks.

Being summer, school was not in session then, but once, perched atop the wagon full of cow manure, as we pulled through the gate, Dad turned around on the tractor and asked if I’d prefer to walk to the meadow in case some of my friends from school were to drive by and see me sitting on a pile of shit. I declined without giving it much thought. I was too tired to walk. And anyway, my day dreams of leaving the farm and finding a life for myself marched through my head on my rides back to the hills where we would commence throwing the poop onto the twenty acre meadow.

I knew I’d probably end up going to nursing school—that would be the most expedient and reliable way to have a profession which supported me. After all, how could anything demand more endurance than what I was doing?

I don’t know why I didn’t give in and take to my bed, or claim sickness and go to the house to rest when I felt exhausted. I know Dad wouldn’t have stopped me. One day, a few years later, as a nursing student on pediatric affiliation in New York City, I sat alone on a green lawn of the Cloisters in the Bronx, studying my textbook, and remembered the green meadow and the manure pile. I remembered we were always on the brink of losing the farm, and I was committed to helping them keep it, anxious to be a part of the effort, anxious to please and be helpful. That should go a long way toward being a good nurse, I thought.

Interview with Rose Elliott

One of the many things I like about this piece is the way it’s so firmly located in a place. As someone raised in the country myself, I think I’ve never lost that sense of the world. Do you find that sense informed your work here?

Oh yes. I strongly believe that place and the people in it when we are young go a long way in shaping who we become. So, it is a lot more than informing the writing for me. Growing up in nature and having our days defined by the work of farming in a community where neighbors and childhood friends shared the same risks and lifestyle has been the foundation from which I see all the rest of the world. From this vantage came my curiosity and motivation to live in urban and other geographical situations, yet I continue to return to the original place for nourishment. Farming and rural living instilled in us, I think, a sense of knowing what basic priorities must be in order to survive, and that shores one up for any endeavor or challenge.

Are there other geographical locations that have had for you this same effect, or an effect rivaling it?

Well, I don’t think anything could rival the developmental influence that being a child of Jefferson County, New York had for me, because it is unique in being bordered by Lake Ontario, The St. Lawrence River which borders Canada, and the Tug Hill Plateau. We lived in the area of famous heavy snowfalls and cold temperatures.

But there were also benefits to the challenge of spending months in New York City on a nursing school affiliation during the mid- sixties. And after that I relished living in several sizable cities in New York State and Virginia. I had to (or wanted to) learn to live in the world and experience a larger life. Then, moving to the countryside of Fluvanna County, Virginia after I’d received my MFA from VCU and had left the nursing profession behind, came with an initial sense of shock, and certainly a need to adjust to living as a country person. We lived there for 6 years, and I found my deeper identity as a writer through being immersed in our somewhat isolated rural neighborhood where wildlife was abundant and the air was really clean.

There’s a sense of family in this memoir, but you don’t make a lot of mention of other siblings. Is that about your birth-place in the family?

As you know, I am the oldest of nine siblings, born within a framework of 17 years—7 girls and 2 boys, the boys being number 5 and 8. I tend to minimize including too many details about siblings in my essays in order to protect their privacy. In this essay, I was 15 at the time, and some of my brothers and sisters were still quite young and didn’t have a role in the hard outdoor work. Inside the house there were many chores they were involved in, while our mother did her house and farm work. Dad and I did get some help from the two sisters closest to me in age for short periods during those 2 weeks, and from Mom when she could. However, I remember it as being mostly me and my father bent on our task.

I like the way the many humble, but skill-requiring tasks of farm life get center stage here. Can you – without giving away further pieces – talk a little bit about what other kinds of farm work have stayed in your awareness?

We farmed in an old fashioned way, mostly because of economic limitations, and partly because these were the methods my father knew. For example, we milked the 25 cows by hand, twice a day, usually with both parents and us 3 oldest girls. All the tasks of animal husbandry: milking, feeding and taking cows to pasture, observing their conditions, when done daily over a period of years (I learned to milk when I was 10, and continued until I was 18 and went away to school), become ingrained in the way you think and relate to animals, and hopefully people too. There were many other well-remembered tasks too: getting in the hay—lifting the heavy bales— cutting and hauling firewood for the stoves that heated our house, picking berries. The tasks were humble, but not humbling or humiliating. One could be proud of having stamina and strong muscles and derive spirituality from living so close to nature.

The last sentence in this piece looks like not only a resolution of this work, but a segue to others. Do you want to talk a little about your nursing stories?

Well, I am working on a book length collection of memoir stories based in my nursing career of 30 years. They include some episodes from three years spent in a hospital-based RN program in Watertown, NY, and 27 years of practice in the areas of critical care, psychiatry and nursing instruction in NY State and Virginia. Those hospital based programs barely exist anymore. The curricula was demanding both academically and clinically, and upon graduation we were prepared to work in almost any area of the nursing profession in any location. My stories range from the rigors of nursing school through a career of intense patient care experiences, and finally to my leaving nursing in my late forties to commit to becoming a writer and teacher of writing.

Can you imagine these home stories in company with nursing stories. What do you think they would feel like, associating with each other?

I am trying to put some of them together in the book length manuscript, which right now has a working title of “What Makes a Nurse?” The title will probably change, but the collection of essays is based on the idea that if place and people help mold our development, how did growing up as farm girls in that post-World War II era groom some of us to be nurses? The challenge with this kind of writing and structuring is to create good enough segues to make the overall piece cohesive for the reader.

Follow us!Share this post with your friends.